ssh -D 4444 -C -N proxy

On school and enterprise networks, restrictions and filtering of your web browsing are nearly synonymous with the warnings about “corporate device, we pwn all your shit.” What if I told you that yes, you can get to that website relatively easily? All you need is a remote system, a little bit of terminal knowledge, and a bit of luck that the huge budget infosec spent on SOC2 compliance didn’t consider DLP via SSH as high enough risk. I mean, really, why would they? If someone’s using SSH out of your network, you’re probably already too far gone and have bigger things to worry about.

teh discovery

I don’t use my local machine for hacking on htb for a variety of reasons. Instead, I use a jumpbox on Linode, which I maintain a constant tmux session on. This makes it super simple for maintaining a consistent environment and I don’t have to mess with digging through history in IRC. Plus, I’m not having to pollute my local systems with a ton of infosec software and Linode is super cool about using instances for this purpose!

Because of this setup, I was initially restricted to doing htb challenges entirely via the terminal. While doable, it can be quite challenging parsing HTML returned by cURL and manually having to chase things down. Eventually, I hit a challenge that I had to have a browser to do – queue the google searching.

Initially I installed chromium on the jumpbox (don’t do this, I’ll explain). This required installing X.Org and enabling XForwarding in SSH. You know, the typical “because of that, all this cruft is required” issue. It’s not terribly difficult to do this setup, but it. is. sloooooooowwww. Especially on a conservatively powered VPS. You’ll be typing and if you’re even moderately fast, you’re going to be waiting a few seconds to see everything you typed in the UI. This is due to network latency and the fact the the remote X server has to re-render the window with every single key press and send all that graphical information back to you. In other words, it’s a ton of bandwidth and this all happens a lot faster locally than over an SSH tunnel.

As I said, that option was slow. But in the vain of learning, it was a valuable experience and taught me how to use some things I didn’t really ever have a purpose for prior to needing said functionality. I was back to hunting for a better solution. I don’t recall exactly what led to the lightbulb moment, but I think it was some random StackOverflow post that mentioned something about proxies via SSH and it got me thinking.

teh h4xx

Not really, this isn’t a hack in the traditional sense. It’s intended functionality and I use some of these settings quite extensively in my day-to-day work when using wireshark and developing API integrations. To begin with you need a few things:

- A local box with a SSH client (I’ve only tested on Linux and Mac – Windows, you’re on your own)

- A remote box with a SSH server

- A browser that you can configure proxy settings in (hopefully your E-Corp doesn’t have this locked down)

K, ready? This is super easy to do. Open your terminal. In said terminal, type:

$ ssh -D 4444 -C -N tj0@jumpbox

Obviously, change tj0 to your username and jumpbox to the IP or domain of your jumpbox. Hell, you can even change 4444 to whatever port you want, as long as it is greater than 1024 (hopefully you understand why). We’ll cover everything that’s going on in that command in detail shortly; let’s get your proxy chain finished first. Open up that configurable browser and find your network settings.

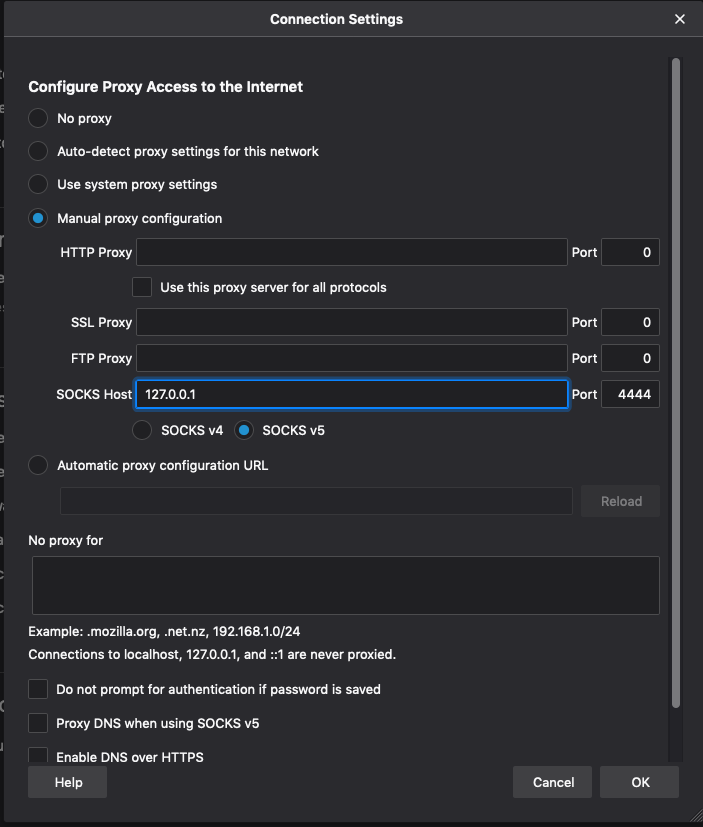

In the case of firefox, click that button and you’ll open the Connection Settings window. Hopefully you’re following, because we’re almost done. Select the Manual proxy configuration radio button, and in SOCKS Host, put 127.0.0.1. In the port box, put whatever port you decided to use for your proxy. Make sure that SOCKS v5 is selected as well. Your settings screen should look like this:

You’re done. Click OK, close preferences, and browse to whatever your heart desires knowing that you’ve defeated one of the most common security measures in corporate and educational IT environments. So what exactly did we just do?

teh deets

Per Wikipedia:

SOCKS is an Internet protocol that exchanges network packets between a client and server through a proxy server. SOCKS5 optionally provides authentication so only authorized users may access a server. Practically, a SOCKS server proxies TCP connections to an arbitrary IP address, and provides a means for UDP packets to be forwarded.

And per man ssh:

-D [bind_address:]port

Specifies a local ``dynamic'' application-level port forwarding.

This works by allocating a socket to listen to port on the local side,

optionally bound to the specified bind_address

...

Currently the SOCKS4 and SOCKS5 protocols are supported, and ssh will

act as a SOCKS server.

As you can see, we established a SOCKS proxy on our local machine which forwards requests to the the server specified at the end of the ssh command. This is why we specified 127.0.0.1 in the connection settings window; we aren’t connecting the browser directly to the remote host. The proxy is responsible for forwarding the browser’s requests to the remote host instead. This provides us the benefit of being able to use local resources for the graphical component of the browser while forwarding all requests to the remote host. In the case of htb, this means you’ll be able to view websites on boxes in the 10.10.0.1/23 subnet.

Pro tip: make sure to set hostnames both locally in /etc/hosts and in /etc/hosts remotely so you can access websites on the htb network with http://target.htb

Continuing on, man ssh says:

-C

Requests compression of all data (including stdin, stdout, stderr,

and data for forwarded X11, TCP and UNIX-domain connections). The

compression algorithm is the same used by gzip(1).

It also goes on to say that compression can slow things down on fast networks – I’ve not noticed any negative impacts from having compression active in my use cases, but this may be due to other variables that are outside the scope of this article.

man ssh:

-N

Do not execute a remote command. This is useful for just forwarding

ports.

The proxy is doing something really basic – it’s whole purpose is to forward the traffic it receives on 127.0.0.1:4444 to tj0@jumpbox. Nothing more, nothing less, just forward that traffic over SSH. The nice thing about this is you don’t have to open any non-standard ports on your remote machine as the pipe connects to the standard SSH port (if you haven’t modified the ssh config, that is). As far as whomever might be monitoring your traffic is concerned, it’s just another SSH connection.

So far, I’ve found this to be the most effective way of regaining some vital functionality for GUI-based applications when interacting with htb challenges. If I felt like dealing with the hassle of keeping sec tools updated locally and the occassional clean up (which would be more often than I already do), I could avoid all of this. The other option is to boot from a live image every time I wanted to hack on something. This way provides much more convenience, and I like that. YMMV.